The zebra finch study system

Since 2004 we study mate choice and reproductive success using up to four captive populations of zebra finches. Two populations are domesticated, presumably going back to imports from Australia in the late 19th century. Two populations are recently wild-derived, based on imports in 1992 and 2016 (Pei (裴一凡) et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022). Domesticated birds tend to be larger (around 16 g compared to 12 g in wild ones) and less shy. Wild-derived birds breed equally fast and well when housed in our large semi-outdoor aviaries.

To study mate choice, we used a range of different approaches. Our studies showed that the key to understanding mate preferences is the direct observation of courtship interactions in communal breeding aviaries. Using motion-detection triggered recordings of a specific perch that the zebra finches use for their courtships, we managed to obtain data from about 80% of all courtship interactions that take place over the course of a breeding season (Ihle, Kempenaers, and Forstmeier 2015; Wang et al. 2020). This enabled us to directly witness mating decisions as they were unfolding. To quantify preferences, we scored the duration of male courtship as well as female responsiveness, which ranged from aggression to copulation solicitation.

An alternative approach we used to study the process of pair formation was to equip all birds with small backpacks carrying a QR-code. This allowed us to continuously locate and track all individuals within a communal breeding aviary. In this setup, the emergence of pair bonds can be seen as a drastic drop in between-individual average distance for a particular male-female pair, that is, pair members increasingly were observed in close proximity of one another (@ Wang et al. 2022).

1 Studying mate choice in zebra finches

1.1 Mate choice in relation to attractiveness

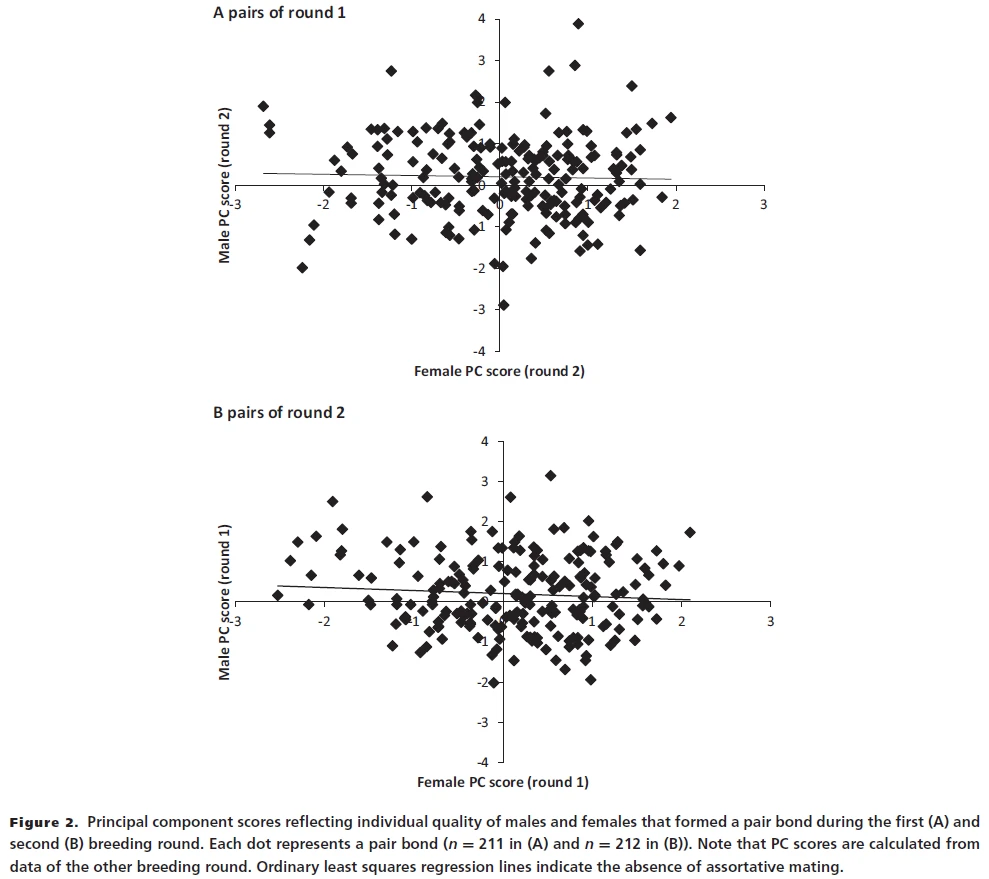

Analysis of female responsiveness in courtship interactions showed that female zebra finches can be very selective. However, counter to what you may think, any two females hardly ever agreed on which male they found the most attractive and which one the least attractive (Ihle, Kempenaers, and Forstmeier 2015; Wang et al. 2020, 2021). Our studies also showed that males do not seem to agree about which female to choose (Wang et al. 2017a https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arx037). Thus, the concept of ‘general attractiveness’ does not seem to apply to zebra finches. Accordingly, we did not observe any tendency that high-quality females would preferentially pair with high-quality males (Wang et al. 2017, 2019), despite the fact that variation in quality can be quite pronounced. We also amplified this variation by experimental inbreeding, which resulted in individuals of obviously low quality in terms of size, ornaments, reproductive performance and viability. Even with this increased variability in quality, we did not find consistent choice for high-quality individuals.

1.2 Mate choice for behavioural compatibility

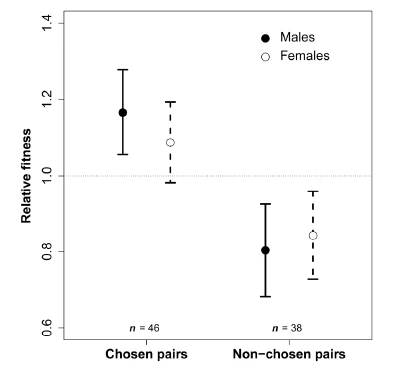

Although two females typically did not agree about which males they liked or disliked, many females showed pronounced individual-specific preferences. To test whether such idiosyncratic preferences resulted in differences in the compatibility of specific pairs, we compared the behaviour and fitness of pairs that had formed through mutual mate choice with those that were randomly arranged via force-pairing for several months. When both types of pairs were released into communal breeding aviaries, most of the “forced pairs” retained their assigned partner, yet the pair relationship was often dysfunctional, characterized by signs of behavioural incompatibility (unwillingness to copulate and to care for the offspring), and resulting in low overall fitness (Ihle, Kempenaers, and Forstmeier 2015). This demonstrated that mate choice for behavioural compatibility is essential in this species, but it remains unclear which phenotypic or behavioural characteristics lead to (in)compatibility of a given pair. A follow-up study focused on courtship song and showed that song was apparently not the target of a female’s individual-specific likes and dislikes (Wang et al. 2021). An early study (Forstmeier 2007) already suggested that females require time to find out which males they like and dislike, reducing the likelihood that readily assessable phenotypes (plumage, song) play a key role. In ongoing work, we try to assess the time window over which individual likes and dislikes develop and we want to find out whether there are “decisive events” that may explain the emergence or the break-up of a pair.

1.3 Mechanisms of species recognition learning

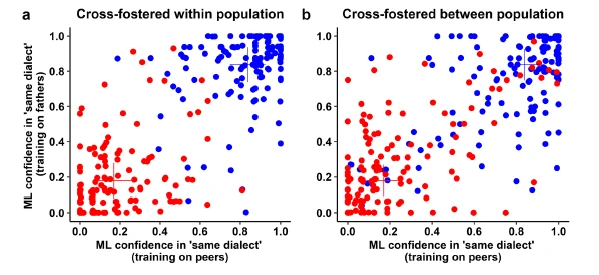

Although females of a given population did not agree about their preference of particular males from their own population (see point 1), they did in fact agree that they disliked males from an unfamiliar population. Hence, when domesticated and recently wild-derived zebra finches are put together in a single aviary, individuals will predominantly mate with a partner from their own population, even when all birds are initially unfamiliar to each other. Using a cross-fostering experiment, we were able to show that birds mated assortatively for their own song dialect, i.e. the song they had grown up with, rather than for body size (Wang et al. 2022). Hence, familiarity with the song, which can rapidly diverge between populations due to cultural drift (much like human languages do), appears to drive assortative mating by population. Making use of this clear preference for the own song dialect, we manipulated the availability of preferred partners to quantify the costs of female choosiness. We found that females can effectively minimize the costs of being choosy when the availability of partners is low (Forstmeier et al. 2021). In further follow-up experiments we now investigate whether familiarizing the birds with the other population in adulthood (mere exposure) can abolish or reduce the own-population preference. We also test whether assortative mating by phenotype can be induced by manipulating early-life experiences with certain phenotypes.

2 Evolutionary genetics of reproductive success

2.1 Proximate causes of infertility and embryo mortality

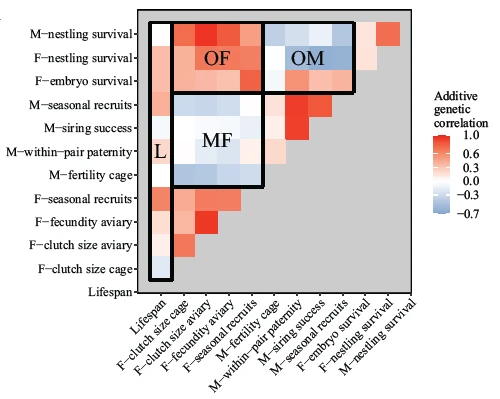

Studying the reproductive performance of four zebra finch populations in captivity, we found surprisingly large variation among pairs – and also among individuals – in the extent to which they suffered from problems with fertility and embryo mortality. Analysing the fate of more than 23,000 eggs, we found that only about 3% of the variance can be attributed to inbreeding, senescence, or poor early-life nutrition (Pei (裴一凡) et al. 2020), implying that most of the individual differences remain unexplained. Approximately one-third of the repeatable differences in reproductive performance appear to be heritable, but selection may fail to remove this genetic variation due to genetic trade-offs between male versus female and offspring fitness traits (sexually antagonistic pleiotropy; (Pei (裴一凡) et al. 2020)).

2.2 Fitness consequences of inversion polymorphisms

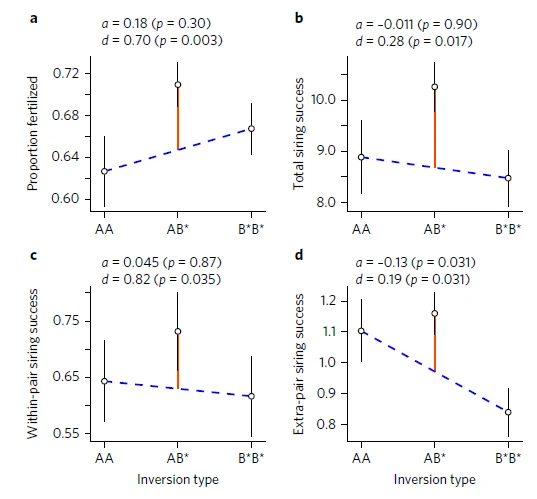

At least 6 out of the 40 chromosomes that make up the zebra finch genome are characterized by an inversion polymorphism, whereby two major structural variants of the chromosome occur in the population with allele frequencies remarkably close to 50%. We investigated how these six polymorphisms affected individual fitness in captivity. Some polymorphisms appear to be maintained by heterozygote advantage ((Knief et al. 2017)), which may arise from antagonistic pleiotropy (Pei et al. 2023), while other polymorphisms appear to be largely selectively neutral (Knief et al. 2016).

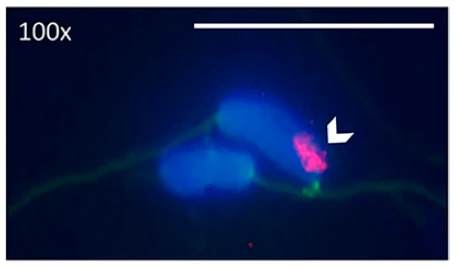

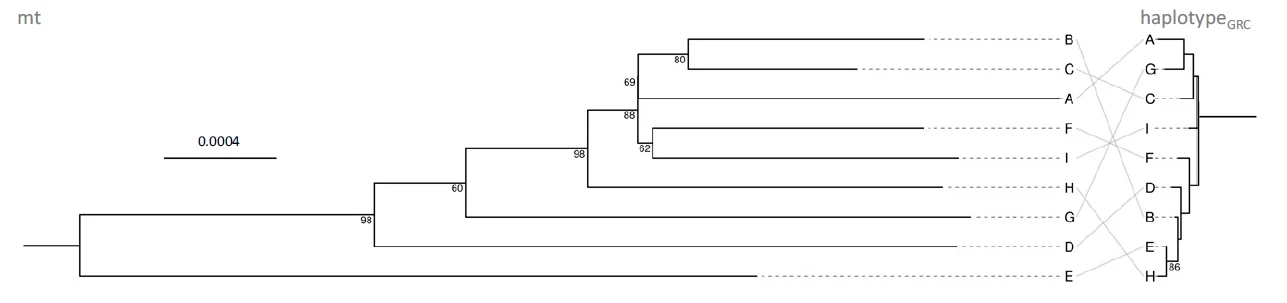

2.3 The role of the germline-restricted chromosome (GRC)

In our search of potential genetic causes of infertility and embryo mortality, we also focused on the little-understood GRC. All songbirds appear to have this special chromosome, which can only be found in the germline (testes, ovaries, early embryos), but is absent from all somatic tissues. By comparing sequencing data from testes and liver, we identified a minimum of 115 genes that are located on the zebra finch GRC. Some of these appear to have resided on the GRC for at least 35 million years of songbird evolution (Kinsella et al. 2019). It was thought that a key feature of the GRC is that it is inherited exclusively through mothers. However, by studying the inheritance of GRC haplotypes, we discovered that paternal inheritance is also possible, and we found that males varied repeatably in the proportion of their sperm that contained a GRC (Pei et al. 2022). In ongoing follow-up studies, we are examining the repeatability, heritability, and fitness consequences of this phenotype in more detail.