Nomadism

Birds are renowned for their remarkable movements spanning vast distances across the globe. Migration – the seasonal transitions between breeding and non-breeding locations – is a well-known phenomenon that fascinates both scientists and the general public.

The phenomenon of nomadism is less known and understudied. Nomadic movements can take place during any time of the year, including the breeding season. Nomadic individuals typically move without a clear pattern in terms of direction or distance. Nomadism can function to explore potential breeding sites and can be driven by environmental factors, such as nest or food availability, or by social dynamics, such as local competition and availability of mates. Some species are nomadic only during a particular stage of their life history.

Our research focuses on nomadic behaviour in shorebirds, a captivating group of birds characterized by an astonishing variety in mating and parental care patterns (Bulla et al. 2016). Our aim is to describe and study the causes and consequences of nomadism in species exhibiting diverse mating systems and life history strategies.

Our study species breed across a wide range of environments, from the Arctic to the Tropics and from the mountain valleys of the Andes to the mudflats of New Zealand. Below is a brief account of each project.

1 The discovery of nomadism in the Pectoral Sandpiper

In 2017 we first described the nomadic movements of the Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos) during the breeding season (Kempenaers and Valcu 2017). You can find a detailed account of how the study unfolded here.

Before our work in Utqiagvik, Alaska, virtually nothing was known about nomadism as a strategy for breeding site sampling. Our study revealed that male Pectoral Sandpipers covered thousands of kilometres in the Arctic to locate suitable breeding sites.

Pectoral Sandpiper males visited many potential breeding sites with large variation in the duration of their stay (tenure) at each site. Male tenure at the breeding site in Utqiagvik correlated positively with the number of fertile females present, and in a given season average tenure correlated with the total number of breeding females in that year, indicating that males make decisions about their movements based on local mating opportunities.

Our current research now aims at understanding the causes and consequences of nomadic behaviour. To this end we first assess whether the phenomenon occurs in other shorebird species. We ask which ecological and life history traits are linked to nomadic behaviour.

2 The Ruff and the White-rumped Sandpiper

We study two polygynous bird species: the Ruff (Calidris pugnax) and the White-rumped Sandpiper (Calidris fuscicollis). Although both are polygynous with female-only parental care, their mating tactics are markedly different.

The Ruff, like the Pectoral Sandpiper, is sexually dimorphic with larger males that engage in intense rivalry. Ruffs come in three morphologically and behaviourally distinct, genetically determined morphs (independents, satellites and female-mimicking faeders). Each morph participates in intricate interactions within small competitive arenas known as leks (Vervoort and Kempenaers 2020). Conversely, in White-rumped Sandpipers males and females do not differ much in size and appearance, and males show aerial courtship displays.

Our preliminary results reveal that both species also exhibit extensive movements during the breeding season.

3 The Red Phalarope and the Eurasian Dotterel

In sequentially polyandrous species females might display nomadic tendencies during the breeding season if this increases their mating opportunities. In contrast to polygynous males, their movements are likely limited because of the time needed to secure a care-giving male and lay eggs.

We investigate the breeding season movements of two polyandrous species: the Red Phalarope (Phalaropus fulicarius) and the Eurasian Dotterel (Eudromias morinellus). In both species, females compete to obtain a male and typically leave soon after they complete a 3-4 egg clutch. However, their post-departure behaviour and the scale of their movements remain largely unexplored.

4 The Long-billed Dowitcher

Most socially monogamous shorebirds return to the same breeding site year after year. The Long-billed Dowitcher (Limnodromus scolopaceus) is a remarkale exception. Both pair members share incubation duties, but females typically leave around hatching and pairs never reunite. The species shows extremely low breeding site fidelity. Thus, we used satellite telemetry to assess their breeding site sampling and the distance between potential nesting sites across years (Kwon and Kempenaers 2023).

5 The Bronze-winged Courser

Exploring multiple breeding sites to increase mating opportunities is not the only reason for nomadism. Some species breed in particular habitats and undertake nomadic movements to find optimal breeding conditions, because the presence of suitable habitat varies widely over time and in space. For these species, nomadism is a response to ecological unpredictability.

The Bronze-winged Courser (Rhinoptilus chalcopterus) is a socially monogamous species found in the African Miombo savannas and shrublands. Notably, they prefer breeding in recently burned patches of land (Kempenaers 2022). We are studying the movements of Bronze-winged Coursers during the breeding season. Our aim is to describe the intricacies of their nomadic lifestyle, and to decipher some of its mysteries, such as how do they find and use burned areas.

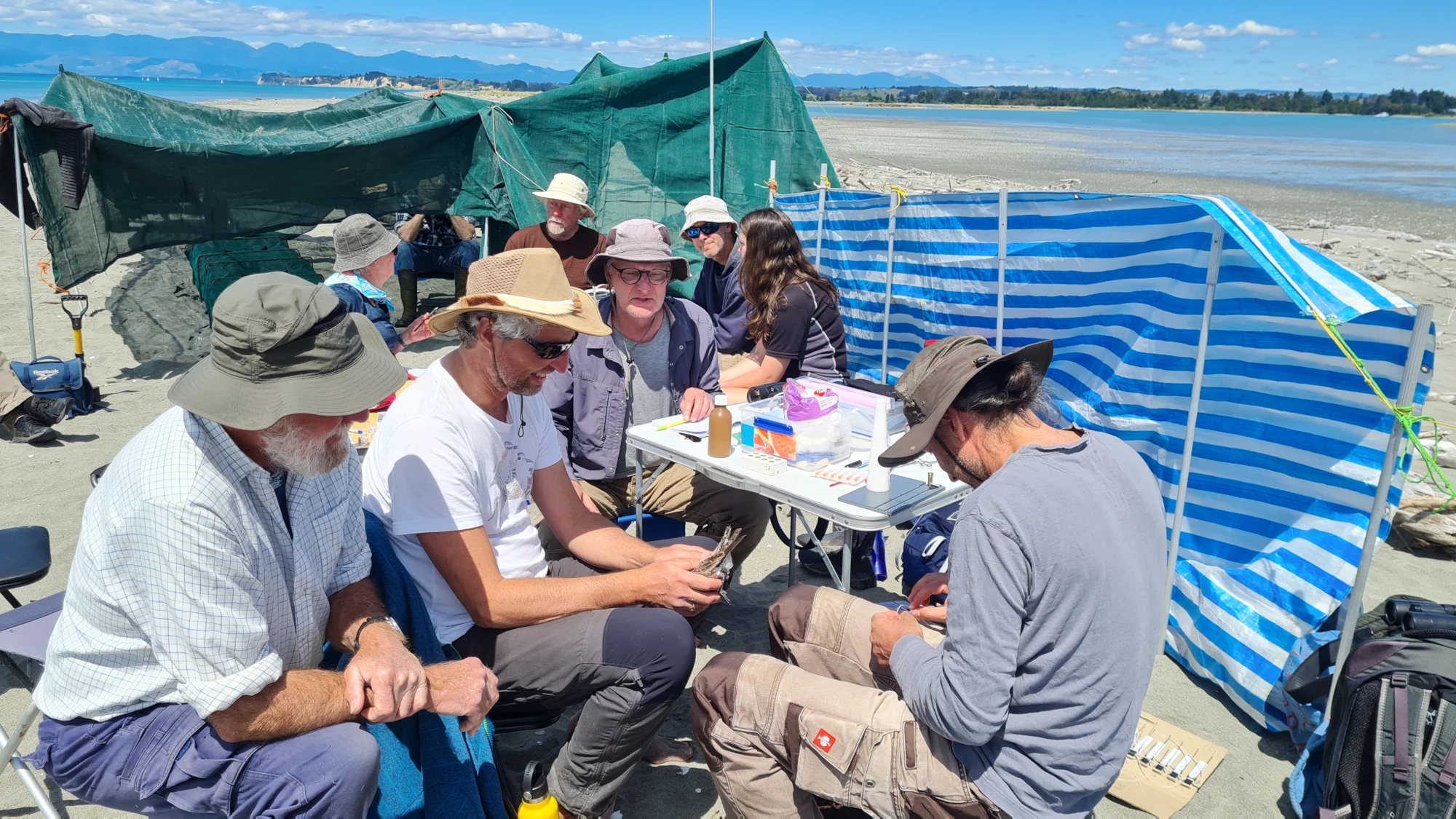

6 The Bar-tailed Godwit

Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa lapponica) are fascinating birds best known for their epic non-stop migration from Alaska to New Zealand. You can find more information on Godwits’ sleep behaviour in flight during these long journeys here. We also study a less known aspect of their behaviour during the non-breeding season in New Zealand that is just as intriguing. Adult Bar-tailed Godwits show high fidelity to the area where they feed and roost, and return to the same location year after year. In contrast, juveniles that arrive to New Zealand after their first long flight from Alaska exhibit remarkable nomadic behaviour. Most individuals visit mudflats across a large part of New Zealand before finally settling at a site for the rest of their life. We hypothesize that the exploratory behaviour of young Bar-tailed Godwits allows them to select their preferred site, possibly influenced by food availability and the social context. For now, the causes and consequences of this behaviour remain enigmatic.

7 Further projects

Nomadism driven by the exploration of potential breeding sites, or the lack thereof, can create differences in the opportunity for local adaptation among species with different mating systems (Kempenaers and Valcu 2017; Kwon et al. 2022) which may lead to different strategies of parental investment. We are currently testing this prediction across shorebirds.

8 Collaborators

Dra. Matilde Alfaro Department of Ecology and Evolution, Vertebrate Zoology Division, School of Sciences, UDELAR, Uruguay

Dra. Matilde Alfaro Department of Ecology and Evolution, Vertebrate Zoology Division, School of Sciences, UDELAR, Uruguay

Dr. Rick Lanctot U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Alaska Migratory Birds Office

Prof. Dr. Theunis Piersma Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research

Prof. Claire Spottiswoode Department of Zoology University of Cambridge, UK and FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology University of Cape Town, SA

Prof. Claire Spottiswoode Department of Zoology University of Cambridge, UK and FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology University of Cape Town, SA

Dr. Paul W. Howey Microwawe Telemetry, Inc., USA

Dr. Paul W. Howey Microwawe Telemetry, Inc., USA

Prof. Phil Batley Massey University, NZ

Prof. Phil Batley Massey University, NZ

Dr. Jesse Conklin University of Groningen, NL

The Australasian Wader Studies Group AWSG, AU

The Australasian Wader Studies Group AWSG, AU

Prof. Terje Lislevand University Of Bergen

Maurizio Azzolini EBN Italia/Dolomiti BirdWatching

Maurizio Azzolini EBN Italia/Dolomiti BirdWatching

Marco Basso, associated to Institute for Environmental Protection and Research

Marco Basso, associated to Institute for Environmental Protection and Research

Paolo Pedrini MUSE - Museo delle Scienze, Trento

Dr. Lorenzo Serra Institute for Environmental Protection and Research

Dr. Lorenzo Serra Institute for Environmental Protection and Research

Gilberto Volcan Parco Paneveggio – Pale di San Martino

Gilberto Volcan Parco Paneveggio – Pale di San Martino